la traduzione italiana è sotto

In this interview, excerpted from a longer conversation that will be featured in the TRAVELOGUE catalogue, art critic, curator, and machinimaker Isabelle Arvers explains why machinima is the ultimate form of détournement.

Isabelle Arvers will participate in a panel titled CRASH: GAME AESTHETICS AND CONTEMPORARY ART on Sunday September 11, 2016 at 11:30 with Valentina Tanni. Click here for more information. Click here to read an interview with Tanni.

Matteo Bittanti: How would you describe the difference between video games and game videos, that is, machinima and video works created with digital games to somebody who is unfamiliar with these cultural artifacts? And what do you find so fascinating about machinima, both aesthetically and conceptually?

Isabelle Arvers: The main difference is interactivity, which is not a feature of machinima, unless you create an interactive machinima experience through an installation or performance. In order to produce a machinima one must use video game technology and play a video game, but the outcome is a linear movie, film, or video. That final product - i.e. the video - can be used as raw material to create something else that could become interactive or not. Most of the times, machinima is non-interactive. So interactivity is a key factor. But there is more...

Once, during a machinima workshop, a student of mine told me something interesting. He said that the main difference between machinima and video games is that with a machinima you can always decide what would happen next, unlike video games where it is “always the same”. I asked what he meant and he said: "After you play the game several times, you know exactly what is going to happen, over and over, and you have almost no control. You just go through the motions, pressing the buttons at the right time". It sounded counterintuitive at first, but I think he was onto something profound. Basically, what he meant is: games are repetitive, machinima is creative.

Another difference lies in the artist's intentions. A gamer and an artist have very different agendas. Playing requires specific skills like coordination and responsiveness. But a gamer basically reacts to predefined inputs. An artist is a true creator, a producer, a so-called prosumer, that is, a producer-consumer. When you make a machinima, you play the role of the content producer: you can express an original idea and use different tools to communicate your message. In other words, you are very active when you produce a non-interactive film. You become a creator rather than a user. A user is a consumer of an “interactive” experience designed by someone else.

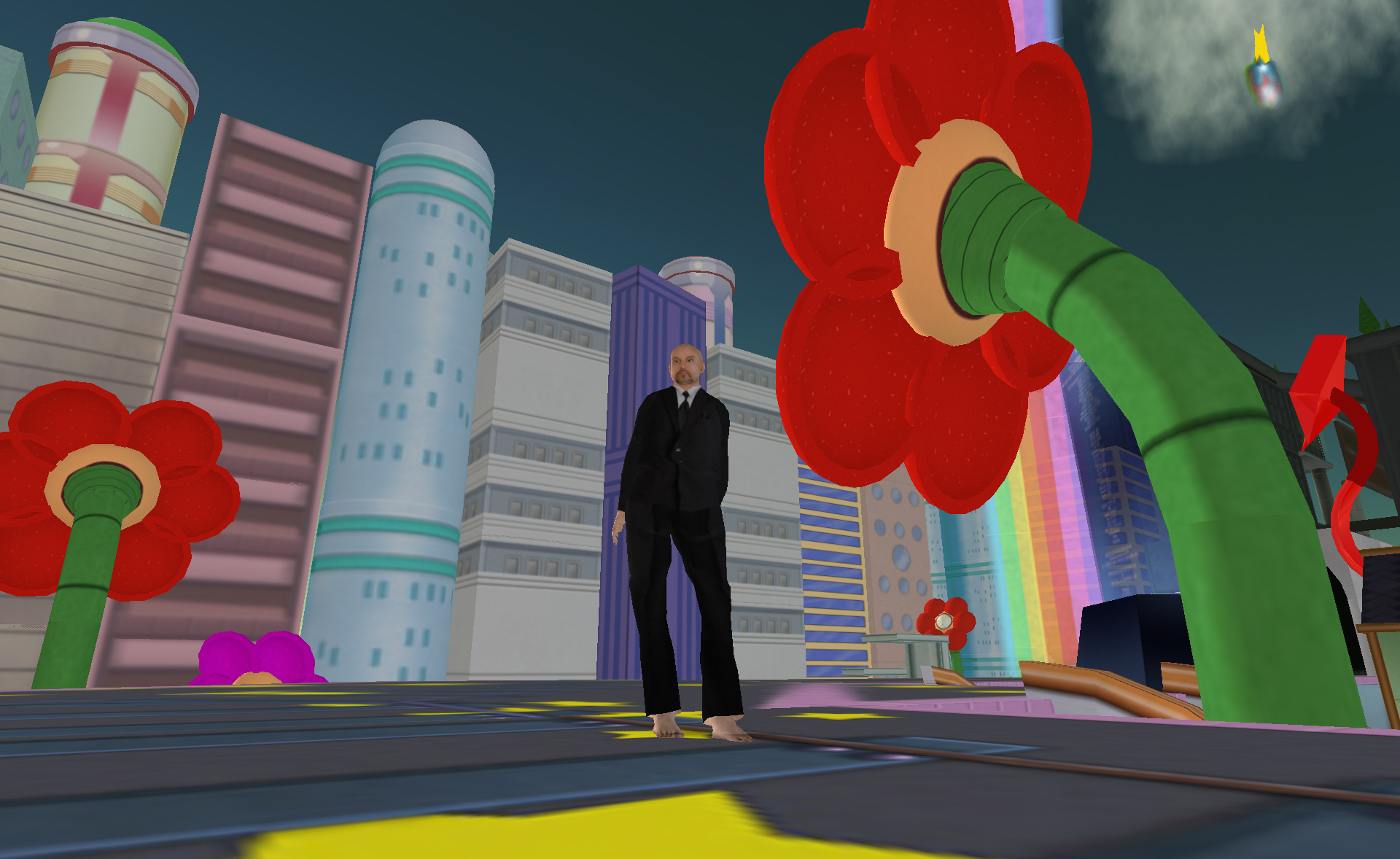

Douglas Gayeton, Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, 2007.

I think that this is the ultimate message of Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, Douglas Gayeton’s machinima documentary filmed in Second Life. In the film, the protagonist is searching for the creator of the virtual world. On his way to enlightenment, he meets several characters. Finally, he discovers that the creators is all of us. The sad part is that we do not get any Intellectual Property benefits from the work we produce: all the rights are owned by the game publishing companies.

In addition to the fact that machinima is a form of reverse-engineering of a video game - to make a machinima is to deconstruct a game and to reconstruct it in a different form - what fascinates me most is the idea of détournement. This situationist technique is about appropriating, reconfiguring, and subverting an existing artifact. To create a machinima is to do something unexpected, something that was not supposed to happen. It’s about transforming an object into something else. To make a machinima is to actively and creatively use a virtual space belonging to popular culture to express different ideas and to deliver an alternative message, because the creator is actively adding a new layer of content onto familiar images. The Situationists used to détourn movies because back in the Sixties cinema was a popular artform, and so, it was able to reach the masses. Today, video games have mass appeal and thus are an ideal medium for détournement.

Matteo Bittanti: Do you consider machinima a genre of video art? Or is it closer to fandom? As a practice, is it confined to game culture? It is separated and/or segregated from the artworld as a whole?

Isabelle Arvers: Machinima can stimulate our minds and deliver different kinds of messages. It enhances our perception and forces us to critically distance ourselves from commercial video and computer games. There is a long tradition of incorporating and using toys and games to make art. Machinima is simply the latest iteration of a process that was pioneered by avant-garde movements like DaDa and Surrealism. Both saw entertainment and play as the most subversive form of art. For them, play was a critical tool.

Video games and Surrealism share many affinities. Consider, for instance, the phenomenon of game dreaming, that is, the tendency of visualizing video game sequences or puzzles while asleep. It is obvious that games influence our mind, perhaps on a subconscious level. To make a machinima is to rearrange the world of a video game, the characters’ behavior, the scenery or the objects. The machinimaker changes the color of the sky, modifies the speed of the animation, or alters the game’s variables. Just like any other artform, machinima influences the way we look at reality. Consider Oscar Wilde’s famous essay, “The Decay Of Lying – An Observation”. All the ideas he discussed in that piece are still valid today. In short, I don’t think that machinima is just an expression of game culture. It is not separated from the artworld and certainly not segregated.

When machinima is not exhibited online or in film festivals but in the context of an art exhibition, it is presented most of the time as video art. But machinima is more like a technique than a genre in itself. Often, when visitors see machinima in an art space and they are unfamiliar with games, they cannot recognize the “source”, that is, games. All they see is three dimensional images. They see computer graphics. But that does not undermine the value of the piece and it certainly does not compromise the viewers' understanding. Additionally, because machinima is still considered a new genre after twenty years of existence, it keeps experimenting and borrowing from the language of film and from non-narrative video art. Today, very few artworks are so influenced by game aesthetics that they cannot be appreciated by an audience unfamiliar with the intricacies of the gaming vernacular. But I also believe that machinima needs to diversity itself and interact with different disciplines in order to become something else, something more, for example, a space that can be inhabited, rather than images on a screen.

Cross By. An immersive exhibition for piano and machinima, June 2016, Aix-en-Provence, France. Isabelle Arvers is responsible for the machinima component of the performance.

Matteo Bittanti: What role does machinima occupy in the current visual landscape? And how did it change overtime?

Isabelle Arvers: I find the evolution of machinima very interesting. Machinima emerged exactly two decades ago within the so-called "hard core" game scene. For several years, it only circulated online. Subsequently, it started to be featured in dedicated festivals and in special programs of major film retrospectives. After 2006, machinima transcended the game culture scene and became a recurrent presence both within the film sphere and the Artworld.

In 2011, I curated a survey show within a larger digital art exhibition and approximately 60% of the artists involved were not gamers at all, but called themselves "film directors". For them, machinima was simply an accessible, inexpensive way to make 3D movies and to express themselves in cinematic terms. In other words, they were making "digital movies". Meanwhile, machinima was mostly ignored by the artworld until 2010, but it became a thing with the rise of the post-internet movement that considered games as contemporary artifacts worthy of critical examination.

In the post-internet scenario, machinima began to inhabit the artworld: it was not an unwelcome guest any longer. It became a staple in biennales and exhibitions. A handful of art galleries now regularly represent artists who make machinima and artworks influenced by 3D graphics, computer animation, and the web. It all began with Miltos Manetas, but artists like Cory Arcangel, Jon Rafman, Larry Achiampong and David Blandy have really blurred the lines between games, machinima, and contemporary art. Interestingly, when machinima entered the artworld, it lost its political edge and became pure aesthetics. Nowadays, young artists use games images, websites or animation as a raw material to produce installations, paintings or video works.

I am happy to say that thanks to the machinima workshops I gave in both Fine Arts and Game Design schools in France, several students who never thought about using machinima to make art have incorporated this techniques in their work. This is particularly exciting because several different contexts - technology, art, cinema, gaming - are now talking to each other in novel ways. I think machinima has now become part of a broader visual landscape than the avant-garde or the so-called underground of the Nineties. Machinima is also related to mash-up culture because of its hybrid nature. It is a mix of collage and reappropriation—indeed the concept itself is a mashup, as it conflates cinema and video games. So, besides the post-internet movement, machinima now belongs to a wider visualscape that includes the DJ and the VJ scene, video clips, remix, and more. Machinima is part of a mix of disciplines, cultures, and practices that, hopefully, will give rise to interesting, not-yet-identified cultural objects.

ISABELLE ARVERS (b. 1972) is a French media art curator, critic and author, specializing in video and computer games, web animation, digital cinema, retrogaming, chiptune music, and machinima. She curated several exhibitions in France and internationally on the relationship between art, video games, and politics including the seminal Gizmoland the Video Cuts (Centre Pompidou, 2001), the Gaming Room at PLAYTIME(Villette Numérique, Paris, 2002), Tour of the Web (Centre Pompidou, 2003), featuring Vuk Cosic and Miltos Manetas among others, Digital Salon. Games and Cinema (Maison Populaire, Montreuil, 2011), GAME HEROES(Alcazar, Marseille, 2011) and several editions of GAMERZ (Aix-en-Provence, France). She also promotes free and open source culture as well as indie games and art games. A graduate of the Institute of Political Studies in Aix-en-Provence and a Postgraduate Diploma in Cultural Project Management of the Paris 8 University, Isabelle Arvers has been researching and working with new media since 1993. A prolific writer, her critical essays have been included in several catalogs, anthologies, and books. Arvers lives and works in Marseille.

Isabelle Arvers parteciperà all'incontro CRASH: ESTETICHE VIDEOLUDICHE E ARTE CONTEMPORANEA che si terrà domenica 11 settembre alle ore 11:30 insieme a Valentina Tanni. Cliccate qui per ulteriori informazioni. Clicca qui per leggere un'intervista con Tanni.

Matteo Bittanti: Come spiegheresti la differenza tra video giochi e giochi video, ossia machinima e altre produzioni audiovisive create con i video game, a chi non possiede grande dimestichezza con questi artefatti culturali? Inoltre, cosa ti affascina in particolare del machinima, sia a livello estetico che concettuale?

Isabelle Arvers: La differenza essenziale è l'interattività, che non è una caratteristica del machinima, a meno che un autore decida di produrre un machinima interattivo attraverso un'installazione o una performance. Anche se un creatore che vuole produrre un machinima deve usare la tecnologia del videogioco nonché "giocare" per effettuare delle riprese, il risultato è un'opera lineare, che si tratti di un filmato, di un corto o lungometraggio. Certo, il video risultante può essere usato come materiale grezzo per creare qualcos'altro, ma nella stragrande maggioranza dei casi, il machinima non è interattivo. Quindi l'interattività rappresenta un importante fattore discriminante. Ma c'è di più...

Una volta, durante un workshop machinima che avevo organizzato in una scuola parigina, un mio studente ha detto una cosa che mi ha colpito molto. Ha dichiarato che la differenza tra il machinima e il videogioco è che in un machinima è possibile "decidere quello che succederà dopo", mentre in un videogioco "è sempre la stessa cosa". Ho chiesto delucidazioni e mi ha risposto: "Dopo aver giocato a un videogioco diverse volte, sai esattamente cosa succederà, le cose si ripetono in modo sempre identico, il giocatore ha un controllo limitato. Si tratta semplicemente di ripetere una sequenza, di premere i pulsanti al momento giusto e poco altro." Anche se all'inizio può suonare bizzarro, le sue affermazioni rivelano una profonda comprensione del potenziale - ma anche dei limiti - del videogioco. In breve: mentre i videogiochi sono ripetitivi, il machinima è creativo.

Un altro importante fattore discriminante riguarda le intenzioni dell'artista. Un giocatore e un artista hanno obiettivi differenti. Il videogiocare richiede abilità particolari come la coordinazione occhio-mano e la capacità di rispondere rapidamente agli stimoli audiovisivi. Ma un giocatore riflette a sollecitazioni predefinite. Per converso, l'artista è un vero creatore, un produttore, un cosiddetto prosumer, contrazione di producer-consumer. Creando un machinima, interpretiamo il ruolo del produttore di contenuti: possiamo esprimere un'idea originale, usando differenti strumenti. In altre parole, siamo davvero "attivi" quando produciamo un film non-interattivo. Siamo "creatori" anzichè "utenti". Un utente è un consumatore di un'esperienza "interattiva" progettata da qualcun altro.

Douglas Gayeton, Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, 2007

Questo è il messaggio profondo di Molotov Alva and His Search for the Creator: A Second Life Odyssey, il machinima doc del regista americano Douglas Gayeton girato in Second Life. Nel suo film, il protagonista è alla ricerca del creatore del mondo virtuale. Lungo il cammino, incontra numerosi personaggi. Alla fine, scopre che il creatore, in realtà, siamo noi. Sfortunatamente, non beneficiamo di alcun vantaggio economico: l'azienda che ha "prodotto" il gioco detiene tutti i diritti. Una beffa.

Oltre ad essere una forma di reverse-engineering di un videogioco - produrre un machinima significa decostruire un videogioco e ricostruirlo in forma differente - ciò che mi affascina di più del machinima è la nozione di détournement. Questa tecnica situazionista consiste nell'appropriarsi, riconfigurare e sovvertire un artefatto esistente. Creare un machinima significa fare qualcosa che non si dovrebbe fare: si tratta di trasformare un oggetto in qualcosa di differente. Produrre un machinima significa usare in modo attivo e creativo uno spazio virtuale che appartiene alla pop culture per esprimere idee alternative, differenti, dato che il creatore aggiunge dei significati assenti nell'opera originale. I Situazionisti utilizzavano la tecnica del détournement per il cinema perché si trattava di una forma popolare di intrattenimento e, come tale, era in grado di raggiungere le masse. Oggi sono i videogiochi ad avere un appeal popolare e per tanto sono il medium ideale per il détournement.

Matteo Bittanti: Consideri il machinima un genere di videoarte? Oppure è un'espressione del fandom videoludico? Si tratta di una pratica limitata alla cultura del videogioco, separata/segregata dal Mondo dell'Arte, ivi inteso in senso beckeriano?

Isabelle Arvers: Il machinima può stimolare le nostre menti e veicolare differenti messaggi. Ridefinisce le nostre capacità percettive e ci costringe a prendere le distanze dai videogiochi commerciali. C'è una lunga tradizione nella storia dell'arte che prevede l'incorporazione di giocattoli e pratiche ludiche all'interno dei processi artistici. Il machinima è semplicemente l'ultima iterazione di un processo che ha tra i suoi pionieri movimenti d'avanguardia come il DaDa e il Surrealismo. Per entrambi questi movimenti, l'intrattenimento e il gioco erano le forme d'arte più sovversive. Per loro, il gesto ludico poteva diventare un potente strumento critico.

I videogiochi e il Surrealismo presentano più affinità di quanto si possa credere. Si pensi, per esempio, al fenomeno dei sogni videoludici, ovvero la tendenza a visualizzare sequenze di un videogioco o la risoluzione di un rompicapo particolarmente difficile durante il sonno... Non ci sono dubbi che i videogiochi influenzano la nostre psiche, forse a livello inconscio. Produrre un machinima significa riconfigurare il mondo di un videogioco, il comportamento dei personaggi che lo abitano, le caratteristiche di uno scenario o degli oggetti ivi contenuti. Il creatore di machinima cambia il colore del cielo, modifica la velocità di animazione o altera le variabili di gioco. Come qualsiasi altra forma d'arte, il machinima influenza il modo in cui percepiamo la realtà. Si consideri il celebre saggio di Oscar Wilde, "Decadenza della menzogna”: tutte le idee che lo scritto ha espresso allora sono ancora valide. Non credo che il machinima sia una mera espressione della cultura videoludica. Non è separato dal Mondo dell'Arte e certamente non segregato.

Quando il machinima non è esibito online o in un festival cinematografico ma nel contesto di un'esibizione d'arte, il machinima è presentato nella maggior parte dei casi come videoarte. Ma il machinima si presenta più come una tecnica che un genere in se stesso. Spesso, quando gli spettatori vedono il machinima in uno spazio artistico e non hanno grande dimestichezza con i videogiochi, non sono in grado di riconoscere il testo sorgente, ovvero i videogiochi. Tutto quello che vedono sono immagini tridimensionali sullo schermo. Computer grafica. Tuttavia, questo non riduce il valore dell'opera né compromette le capacità degli spettatori di comprendere ed apprezzare ciò che vedono. Inoltre, dato che il machinima è tutt'ora considerato un "nuovo genere" dopo vent'anni di esistenza, gli artisti che lo utilizzano sperimentano e prendono in prestito aspetti del linguaggio cinematografico o della videoarte. Oggi, poche opere machinima sono così influenzate dal videogioco da risultare incomprensibili per un'utenza completamente a digiuno di cultura videoludica. Ritengo tuttavia che il machinima debba diversificare la propria estetica e interagire con differenti discipline al fine di diventare qualcos'altro, qualcosa di più, per esempio, diventando uno spazio abitabile anziché mere immagini su uno schermo.

Isabelle Arvers, machinima, #labRes2015. Cfr. http:// ruralscapes.net/isabelle-arvers/