Filmmakers and video artists engaged in the practice of appropriating, repurposing, and remixing video games are encouraged to send us their work for consideration. All submissions will be judged by an international panel of jurors comprising scholars, curators, and critics. A Critics' Award will be awarded to the most groundbreaking work.

EVENT: THE MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL MMXXII IS NOW HAPPENING

The MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL MMXXII returns with a hybrid format —both online and in situ screenings — after a long disruption in the face of an unprecedented global crisis. The festival program is now online: 25 works of machinima and game video created by 21 artists representing 9 countries are featured in two distinct sections — EVERYTHING MUST CHANGE (March 26 2022, IRL) and FOR EVERYTHING TO STAY THE SAME (March 21-27 2022, online) — for a total of 11 programs.

Below is a breakdown of all the features:

EVERYTHING MUST CHANGE (Museum of Interactive Cinema, Milan, March 26 2022): MACHINEMA (MACHINE CINEMA), BRAND NEW YOU ARE RETRO, and MADE IN ITALY

FOR EVERYTHING TO STAY THE SAME (March 21-27 2022, online): THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE AI, BAD TALES, SONG TO SONG, GAME VIDEO ESSAY, IDENTITIES/INTIMACIES, HISTORIES/HERSTORIES, NO DRAMA, PLEASE, and GAME OVER PRESENTS: THIS IS NOT A GAME.

This year the curators are unlocking the various features gradually, like levels of a video game. The online section comprises seven back-to-back features and one special screening.

The first two — THE GOOD THE BAD AND THE AI — featuring works by Phil Rice (US) and Beatrice Carpina (IT) — and SONG TO SONG - featuring machinima by Paolo Santagostino (IT) and Lorenzo Antei (IT) are now available.

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL MMXXI (MARCH 15-21 2021, ONLINE)

MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL MMXXI

FROM VIDEO GAMES TO VIDEO ART

March 15-21 2021

Online event

Milan, Italy

An official event of the Milan Digital Week, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL showcases audiovisual non-interactive works produced with video games otherwise known as machinima. This year, the retrospective will take place exclusively online due to the ongoing pandemic. The program feature six sections: IN FOCUS, GAME VIDEO ESSAY, GRAND THEFT CINEMA, [CODE] CONFINEMENT, GLITCH 'N SCAPES, and SPECIAL SCREENING. Selected artists include Iono Allen, Adonis Archontides, Nilson Carroll, Nick Crockett, Luca Giacomelli, Gina Hara, Kamilia Kard, Chris Kerich, Felix Klee, Eddie Lohmeyer, Luca Miranda, Alessandra Porcu, Riccardo Retez, Alessandro Tranchini, Lena Windisch, XUE Youge (薛 又 戈), and HU Yu (胡 煜).

The main theme of the MMXXI edition, From Video Games to Video Art, alludes to the variety of artistic manipulations of video games and their evolution into game videos. The authors deconstruct digital environments by subverting and reinterpreting their constitutive codes. From a matrix of postmodern cinematic citations embedded in Grand Theft Auto V to the notion of “limbo” as an existential condition, the selected machinima critically examine the logic, politics, and ideologies of the contemporary moment, triggering unexpected epistemological short circuits.

As in previous years, a Critics’ Choice Award will be awarded to the most significant machinima by an international jury composed of critics, curators, and academics: Valentino Catricalà (Artistic Director of the Media Art Festival in Rome), Marco De Mutiis (Digital curator of the Fotomuseum Winterthur), Stefano Locati (member of the Scientific Committee of the Ca 'Foscari Short Film Festival of Venice and Co-director of the Asian Film Festival of Bologna), Henry Lowood (Curator for the Germanic Collections and the History of Science and Technology Collections at Stanford University), and Jenna NG (Professor of Film and Interactive Media at the University of York).

Curated by Matteo Bittanti with Gemma Fantacci, Luca Miranda, and Riccardo Retez, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2021 is an official event of Milano Digital Week organized in collaboration with GAMESCENES. Art in the age of video games and the M.A. in Game Design at IULM University. A follow-up to the 2016 exhibition GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL brings to Milan idiosyncratic video works that lie at the intersection of video art, cinema, streaming, and digital games.

All the works will be accessible for free on festival website from 15 to 21 March 2021.

LINK: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL

BOOK: MACHINIMA VERNACOLARE

We’re happy to announce the release of volume one in the new series GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES edited by Matteo Bittanti: Machinima vernacolare by Riccardo Retez.

Available both on Amazon and Blurb in Italian, Machinima vernacolare examines the relationship between cinema, television, and video games, focusing on fandom productions that made machinima into a recognizable expression of popular culture and one of the most popular examples of user generated content.

Retez focuses on Grand Theft Auto V’s Rockstar Editor, a popular video editing tool used to created countless machinima. The author describes the production, consumption and distribution practices within an increasingly complex media environments. The analysis, which is accompanied by six case studies, demonstrates that far from being passive users, video game players can become guerrilla video makers.

Born and raised in Florence, Riccardo Retez received a Master's Degree in Television, Cinema and New Media from the IULM University of Milan in 2019 and a Degree in Graphic Design and Multimedia from the Free Academy of Fine Arts in Florence in 2017, where he studied the relationship between technology-based art practices culture and the humanities. Passionate about cinema, video games and visual culture, in the past five years Riccardo produced, edited, and directed several short films and video clips. Machinima vernacolare is his first book.

GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES examines the complex interaction between digital gaming and the visual arts through academic contributions situated at the intersection of different disciplinary areas – game studies, art criticism, visual studies, media studies and cultural studies – and gives voice to a new generation of researchers as well as established scholars. Both a critical and creative laboratory, GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES promotes open dialogue, constructive debate, and sometimes idiosyncratic investigations of ideas, practices, and artefacts that – by their very nature – occupy different layers of today’s visual culture. Using a comparative rather than specialized approach, GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES probes the most diverse visual experiences inspired by digital gaming.

To learn more about Machinima vernacolare, please visit this page, which includes a video walkthrough (in Italian).

To learn more about GAME VIDEO/ART STUDIES, please click here.

Siamo felici di annunciare la pubblicazione del primo volume della nuova collana GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES diretta da Matteo Bittanti: Machinima vernacolare di Riccardo Retez.

Disponibile su Amazon e Blurb in lingua italiana, Machinima vernacolare esamina il rapporto tra cinema, televisione e videogiochi e le dinamiche del fandom videoludico che ha elevato il machinima a una marca di riconoscimento delle produzioni user generated.

Retez esamina il Rockstar Editor, il software di montaggio video integrato a Grand Theft Auto V (2013),. L’autore descrive le dinamiche di produzione, consumo e distribuzione del machinima all’interno di un ecosistema mediale sempre più complesso. L’analisi, impreziosita da sei studi di caso, attesta che gli utenti di videogiochi non sono consumatori passivi di testi audiovisivi, bensì soggetti attivi in grado di comprendere e manipolare i significati variabili codificati in tali testi, proponendo sofisticati remake.

Nato e cresciuto a Firenze, Riccardo Retez ha conseguito una Laurea Magistrale in Televisione, cinema e nuovi media presso l’Università IULM di Milano nel 2019 e una Laurea in Graphic Design e Multimedia presso la Libera Accademia di Belle Arti di Firenze nel 2017, dove ha studiato la relazione tra la cultura tecnico-artistica e tradizione umanistica. Appassionato di cinema, videogiochi e culture visive, Riccardo ha realizzato numerosi cortometraggi e videoclip. Machinima vernacolare è il suo primo libro.

Laboratorio critico e creativo, la collana GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES promuove un dialogo aperto, un confronto costruttivo e una disamina non necessariamente ortodossa di temi, pratiche e fenomeni che, per loro natura, s’intersecano con differenti livelli della cultura visiva. Privilegiando un approccio comparativo anziché specialistico, GAME VIDEO/ART. STUDIES scandaglia le più diverse esperienze mediali ispirate dal e al videogioco per dare voce a una nuova generazione di ricercatori così come a studiosi consolidati.

Per ulteriori informazioni su Machinima vernacolare, visitate la pagina del libro, che contiene contenuti extra, tra cui una video presentazione dell’autore.

Per ulteriori informazioni su GAME VIDEO/ART STUDIES, cliccate qui.

CALL FOR ENTRIES: MACHINIMA FILM FESTIVAL 2021

The fourth edition of the MACHINIMA FILM FESTIVAL will once again take place at IULM University (Milan, Italy) during the Milano Digital Week, which celebrates the driving forces that are reshaping art, culture, and technology of Italy’s main engine.

Filmmakers and video artists engaged in the practice of hijacking, repurposing, and remixing video games are encouraged to submit their work for consideration. All submissions will be evaluated by an international panel of jurors comprising scholars, curators, and critics. A Critics' Award will be awarded to the most groundbreaking work.

Screenings of selected machinima will be curated around different themes and presented across different sections. The most interesting submissions are those which seek to capture or highlight a specific facet of contemporary life, from politics to art, from violence to creativity, from technology to ideology, through the aesthetic lenses of digital gaming.

The deadline for submissions is December 15, 2020.

The full program will be announced in February 2021.

The MMF is organized in collaboration with GAMESCENES. Art in the age of video games.

Please carefully read our simple submission guidelines and requirements below before sending your work.

INTERNATIONAL OPEN CALL FOR NEW MEDIA ARTWORKS

GUIDELINES:

INTERNATIONAL OPEN CALL FOR NEW MEDIA ARTWORKS GUIDELINES:

The Milan Machinima Festival defines machinima as any digital video made using video game technology (game engines, game tools, assets such as characters, items, environments etc.).

A preference is given to machinima created with/in video games rather than virtual worlds such as Second Life.

Submissions must be 10 minutes or less in length.

The minimum duration is 2 minutes.

Submissions must have been produced between January 1, 2020 and December 15, 2020.

Multiple versions of the same machinima will not be considered.

Acceptable submission formats: digital video files only.

Acceptable exhibition formats: mp4, avi, mpg, Quicktime file (ProRes 422).

Each submission requires a one-time, nominal submission fee of 15 euros. Submissions that have not been accepted will not be refunded.

The applicant holds the sole responsibility of copyright clearance of any copyrighted material in the machinima.

Each submission must include an accompanying artist statement/description no longer than 500 words in English.

The MMF is under no obligation to provide comments regarding submitted machinima to any applicant.

All applicants must complete the official festival submission form located on FilmFreeway.

Submission deadline: December 15, 2020

NEWS: WELCOME TO THE 2020 EDITION OF THE MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL

THE 2020 EDITION OF THE MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL IS NOW AVAILABLE ONLINE!

From May 25th until the 30th 2020, the work of 25 different artists from 13 nations are exhibited online in 6 different programs. Click here to see the full lineup. Most of these works have never been presented in Italy before.

An official event of Milano Digital Week, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is organized in collaboration with GAMESCENES. Art in the age of video games and the M.A. in Game Design at IULM University. A follow-up to the 2016 exhibition GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY, the festival brings to Milan idiosyncratic video works that lie at the intersection of video art, cinema, and digital games.

The 2020 MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is presented by FANTAGEMMA, Gemma Fantacci’s alter ego.

Start watching now!

Follow us on Instagram & Twitter

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2020 GOES FULLY DIGITAL

We are happy to announce that the 2020 edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL - which was postponed due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic - will indeed take place. And sooner than later.

From Monday 25 till Saturday May 30 2020, the entire program will be fully available on the Festival website. This year, the work of 25 artists from 13 countries will be presented in 6 sections: GAME VIDEO ESSAY A, GAME VIDEO ESSAY B, THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, AND THE UNREAL plus three special programs (IN FOCUS).

The MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is part of the revamped Milano Digital Week 2020.

Click here to read the full program

SIAMO FELICI DI ANNUNCIARE CHE L’EDIZIONE 2020 DEL MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL PRECEDENTEMENTE POSTICIPATA PER VIA DELLA PERDURANTE PANDEMIA COVID-19, SI SVOLGERÀ ANCHE QUEST’ANNO.

Da lunedì 25 a sabato 30 maggio, l’intero programma sarà infatti interamente disponibile sul sito del festival. Il programma dell’edizione 2020 include opere realizzate da 25 artisti provenienti da 13 nazioni suddivise in 6 sezioni: GAME VIDEO ESSAY A, GAME VIDEO ESSAY B, THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, AND THE UNREAL e tre approfondimenti (IN FOCUS).

Il MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL è un evento ufficiale della Milano Digital Week.

Clicca qui per leggere il programma completo.

NEWS: INTRODUCING VRAL

We are happy to announce VRAL, a uniquely curated game video experience, available for free on the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL website offering screenings of machinima created by artists and filmmakers whose work lies at the intersection of video art, cinema, gaming, and other visual practices.

The program features exceptional machinima selected based on their cultural relevance, artistic achievement, and innovative style. Often presented only in the context of festivals, exhibitions, and surveys, these works best represent the variety, ingenuity, and creativity of game-based video practices. A space providing access to diverse and innovative voices, VRAL is an online-only supplement to the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL. Throughout the year, VRAL celebrates a new generation of digital filmmakers and artists engaging with video game-based technologies, aesthetics, and practices.

The project comprises exclusive interviews, image galleries, and an archive.

VRAL begins April 25 2020 with the world premiere of Rapid Transit: Preface by Victor Morales.

LINK: VRAL

CFP: MACHINIMA, THE STATE OF THE ART

The 2020 edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL will be followed by the release of a printed bilingual (English and Italian) publication later this year featuring critical contributions on machinima. The book/catalog will be edited by Matteo Bittanti and Gemma Fantacci.

Scholars, critics, artists, and curators are invited to submit an extended abstract (between 500-1000 words excluding references) or full papers to matteo.bittanti@iulm.it either in English or Italian.

Timeline:

April 15, 2020 Abstract submission deadline (full papers are also accepted);

May 15, 2020: Notification of acceptance/rejection sent to authors;

July 1, 2020: Full paper submission deadline;

Sept 1, 2020: Review deadline;

Oct 1, 2020: Deadline for edited papers.

Possible topics include:

Vernacular machinima vs. avantgarde machinima

Exhibition & screening of machinima

Art historical perspectives on machinima

Recording and sharing of in-game performances

The evolution of in-game video editors

Critical analysis of an artist's oeuvre/work

The changing audiences of machinima

Machinima as mash up/remix culture

Inquiries may be directed to matteo.bittanti@iulm.it

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2020 (MARCH 09-13 2020, MILAN, ITALY)

We are delighted to announce the full program of the 2020 MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL.

The event takes place between March 09-13 2020 at IULM University in two separate locations: the Contemporary Exhibition Hall and the Sala dei 146, both located in the IULM Open Space building. Both venues are open to the public, but we kindly encourage attendees to register for the screening on Friday March 13 2020 in the Sala dei 146 as seats are limited.

Please note that each day features a different program. The festival is bookended by two sections titled GAME VIDEO ESSAY A (March 09 2020) and B (March 13 2020), after a successful run in the 2019 event of the4 same title. From Tuesday until Thursday we will present an indepth look at four artists whose daring, groundbreaking, unclassifiable work has redefined the aesthetics of machinima: Larry Achiampong, David Blandy, Jacky Connolly, and Oscar Wagenmans in the context of the Contemporary Exhibition Hall.

The festival concludes on Friday March 13 with The Weird, The Eerie, and The Unreal, which includes a selection of the most impressive works submitted this year and evaluated by our international jurors. During the screening, we will announce the 2020 Critics’ Award.

SCHEDULE

Monday March 09 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY A

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Tuesday March 10 2020

FOCUS: SAVEME OH

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Wednesday March 11 2020

FOCUS: JACKY CONNOLLY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Thursday March 12 2020

FOCUS: LARRY ACHIAMPONG & DAVID BLANDY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Friday March 13 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY B

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Free Entry

Friday March 13 2020

THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, THE UNREAL

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

18:00 - 20:00 Please RSVP

Click here to read the full program

Siamo lieti di annunciare il programma completo del MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2020.

L'evento si svolge dal 09 al 13 marzo 2020 presso l'Università IULM in due sedi separate: la Contemporary Exhibition Hall e la Sala dei 146, entrambe situate nell'edificio IULM Open Space. Le sedi sono aperte al pubblico, ma invitiamo i visitatori a registrarsi per la proiezione di venerdì 13 marzo 2020 nella Sala dei 146, poiché i posti sono limitati. Si prega di notare che ogni giorno è previsto un programma diverso. Il festival è incorniciato da GAME VIDEO ESSAY A (09 marzo 2020) e B (13 marzo 2020), dopo il successo dell'esperienza nel 2019.

Da martedì a giovedì presenteremo uno sguardo approfondito su quattro artisti il cui lavoro innovativo ha ridefinito l'estetica del machinima: Larry Achiampong, David Blandy, Jacky Connolly e Oscar Wagenmans nel contesto della Contemporary Exhibition Hall.

Il festival si conclude venerdì 13 marzo con The Weird, The Eerie e The Unreal, che comprende una selezione delle opere più significative presentate quest'anno e valutate dai nostri giurati internazionali. Durante la proiezione, verrà annunciato il Premio della Critica 2020.

CALENDARIO

Lunedì 09 marzo 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY A

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Martedì 10 marzo 2020

FOCUS: SAVEME OH

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Mercoledì 11 marzo 2020

FOCUS: JACKY CONNOLLY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Giovedì 11 marzo 2020

FOCUS: LARRY ACHIAMPONG & DAVID BLANDY

Contemporary Exhibition Hall (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Venerdì 13 marzo 2020

GAME VIDEO ESSAY B

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

09:00 - 19:00 Ingresso gratuito

Venerdì 13 marzo 2020

THE WEIRD, THE EERIE, THE UNREAL

Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE)

18:00 - 20:00 Registrazione richiesta

Cliccate qui per leggere il programma completo

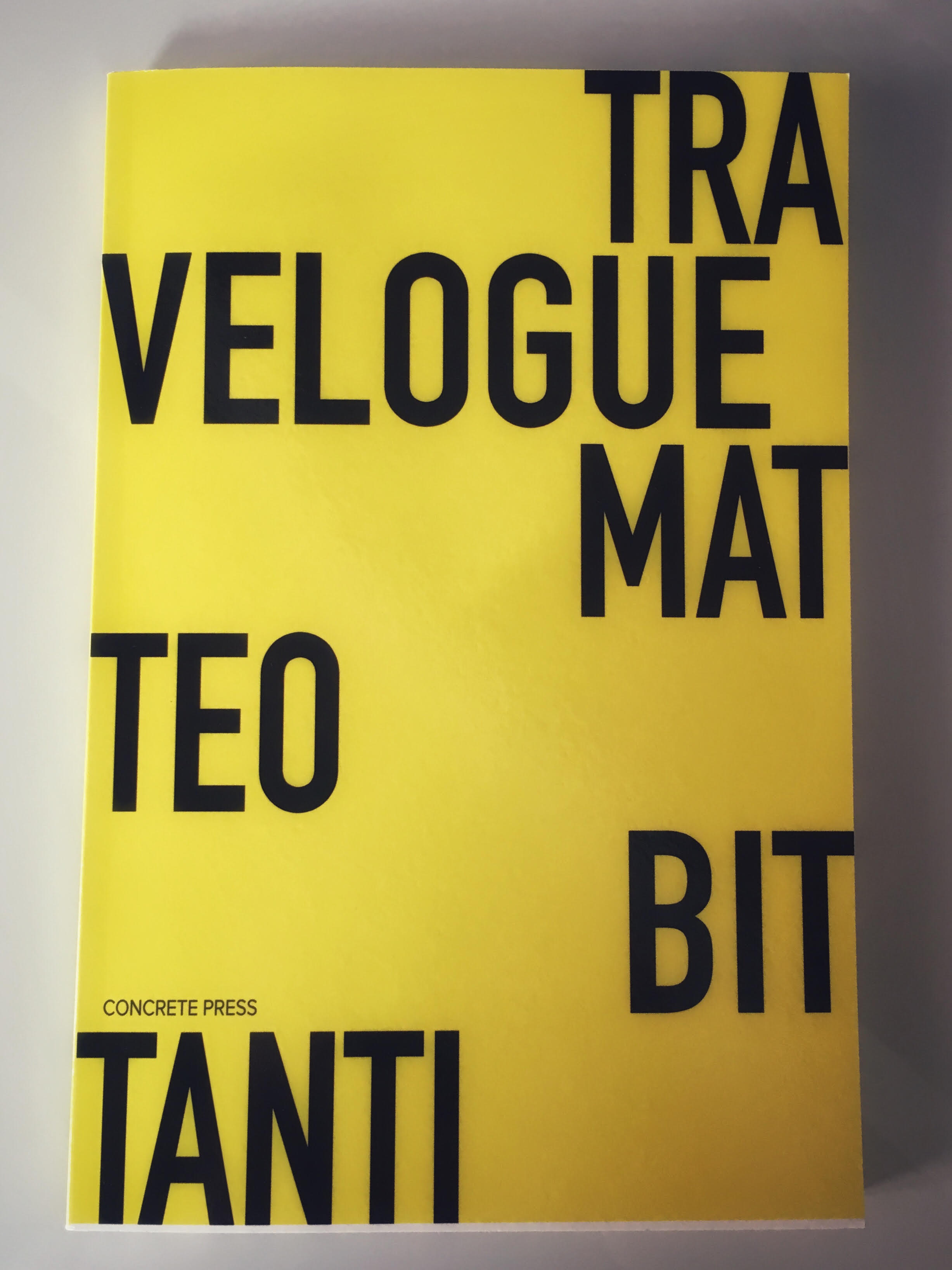

BOOK: TRAVELOGUE CATALOG NOW AVAILABLE!

TRAVELOGUE is now available from Concrete Press.

This book is an extended catalogue of the exhibition TRAVELOGUE (Mantua, September 7- 11 2016) featuring artworks by Max Almy and Teri Yarbrow, Hugo Arcier, Dave Ball, William Beaudine, Bob-Bicknell Knight, COLL.EO, Clint Enns, Matthew Hillock, JODI, Kristin Lucas, Victor Morales, Leonardo Sang, Palle Torsson. Available in bilingual edition (English and Italian) TRAVELOGUE is the follow-up to MACHINIMA. 32 conversazioni sull'arte del videogioco, which was released in 2017.

You can purchase a copy of TRAVELOGUE on Blurb orAmazon US.

It will soon be available on Amazon Italy.

MEDIA: SIGHT & SOUND ON THE ART OF MACHINIMA

"Machinima – a portmanteau of machine and cinema – the process of using real-time computer graphics engines to create a cinematic production [...] has existed for as long as in-game recording has been possible." Matt Turner aka Lost Futures provides a historical and critical overview of machinima, a digital form of filmmaking that lies at the intersection of experimental cinema and video art that began with Miltos Manetas’ Miracle, for Sight & Sound magazine. A must read.

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL (MARCH 15 2019, MILAN, ITALY)

The MACHINIMA FILM FESTIVAL returns to Milan on March 15 2019 during the Milano Digital Week.

This event showcases artistic excellence in contemporary digital image culture and experimental new media art through several on-screen works. The MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is the only event in Italy solely dedicated to machinima, a genre of digital video art created by appropriating and manipulating video games that emerged in the mid-1990s.

The theme of the 2019 program is the UNCANNY, the perceptual phenomenon caused by experiences that are at once familiar and alien. Haunting hallucinations pervade an eclectic program in which glitches, shocks, and disturbing repetitions become a metaphor for societal chaos in the age of algorithms, surveillance capitalism, and artificial intelligence. These disquieting narratives question the relationship between authenticity and performance, identity and self preservation in everyday (digital) life. Two longer documentary works examine the unexpected side (effects) of virtual gaming and the current fascination with technology’s dystopian impact on public and private life.

The 2019 lineup includes an impressive roster of short films and longer works by national and international artists and filmmakers such as Lisa Carletta (Paradise Found), COLL.EO (Reasonable), Joseph DeLappe (Elegy), Kara Gut (Resonant Flash, Ismaël Joffroy Chandoutis (Swatted), Chris Keric (Dynamic Kinetic Sculptures), Luigi Marrone (Avatar_Ascension), Luca Miranda (Alma), Leonhard Müellner (Operation Jane Walk), Bram Ruiter (Perpetual Spawning), Brenton Smith (Crashforms Studies), Petra Szeman (How to Enter a Fictional Realms), Twee Whistler (Edgy Time with Mom), and Brent Watanabe (Possessions). The vast majority of these artworks have never been shown in Italy before.

An international panel of critics, curators, and academics contributed to the selection and evaluation process, including Valentino Catricalà (Artistic Director of the Media Art Festival in Rome), Marco De Mutiis (Digital curator at Fotomuseum Winterthur), Stefano Locati (member of the Scientific Committee of the Ca’ Foscari Short Film Festival in Venice and Director of the Asian Film Festival in Bologna), Henry Lowood (Curator for the Germanic Collections and the History of Science and Technology Collections at Stanford University), and Jenna NG (Professor of Cinema and Interactive Media at the University of York).

Among the festival’s highlights is Jenna NG’s keynote talk on March 13 2019 as part of the ongoing GAME TALKS series at IULM. Titled MACHINIMA AND THE ALLURE OF EPHEMERALITY: GAMEPLAY, LIVE STREAMS, AND DIGITAL CULTURE, the talk will address the explosion of interest in the live streaming of gameplay as illustrated by the popularity of Twitch, whose latest number of daily active users has reached 15 million, as well as other major platforms such as YouTube Gaming, Mixer, and Facebook Live. Specifically, the talk will link the current phenomenon of video game live streams with machinima and its origins in game demos and captured video game play, arguing not only for live streams to be the next logical evolution for machinima, but also for a critical theorisation of screen media that pursues a realist trajectory, one which potentially works its way from neorealist cinema to machine vision.

Sponsored by the City of Milan, Department of Digital Transformation and Public Services, the Milano Digital Week celebrates the driving forces that are reshaping work, leisure, and learning. By highlighting the interplay behind production and consumption made possible by digital technology, MDW connects citizens, companies, institutions, universities, and research centers.

The MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL was curated by Matteo Bittanti (Artistic Director), presented by Gemma Fantacci (Communication Manager), and organized by the Master of Arts in Game Design at IULM University. Screenings take place in Sala dei 146 located in the IULM Open Space. Admission is free upon registration.

Il MACHINIMA FILM FESTIVAL torna a Milano il 15 marzo 2019 nell'ambito della Milano Digital Week 2019.

La rassegna presenta lo stato dell’arte della cultura visiva digitale contemporanea e la new media art sperimentale. Il MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL è l’unico evento italiano interamente dedicato al machinima, un genere di video arte prodotta attraverso l’appropriazione e manipolazione dei videogiochi che si è affermata a partire dalla seconda metà degli anni Novanta.

Il tema dell’edizione 2019 è UNCANNY, il fenomeno percettivo che contraddistingue esperienze insieme familiari e anomale, declinato all’interno di un programma eclettico in cui glitch, shock e inquietanti ripetizioni alludono al crescente senso di smarrimento sociale nell’era degli algoritmi, dei Big Data e dell’intelligenza artificiale. In queste opere, lo spazio ludico genera narrazioni alternative, sollecitando una riflessione sul rapporto tra autenticità e performance, identità e preservazione del sé. Due mediometraggi esaminano gli effetti collaterali del videogioco e la fascinazione contemporanea per la dimensione distopica della tecnologia.

Il programma dell’edizione 2019 include una selezione di cortometraggi e mediometraggi realizzati da artisti nazionali e internazionali come Lisa Carletta (Paradise Found), COLL.EO Reasonable), Joseph DeLappe (Elegy), Kara Gut (Resonant Flash, Ismaël Joffroy Chandoutis (Swatted), Chris Keric (Dynamic Kinetic Sculptures), Luigi Marrone (Avatar_Ascension), Luca Miranda (Alma), Leonhard Müellner (Operation Jane Walk), Bram Ruiter (Perpetual Spawning), Brenton Smith (Crashforms Studies), Petra Szeman (How to Enter a Fictional Realms), Twee Whistler (Edgy Time with Mom), e Brent Watanabe (Possessions). La maggior parte di questi audiovisivi sono inediti in Italia.

Al processo di selezione ha contribuito una giuria internazionale composta da critici, curatori e accademici: Valentino Catricalà (Direttore artistico del Media Art Festival di Roma), Marco De Mutiis (Digital curator del Fotomuseum Winterthur), Stefano Locati (membro del Comitato scientifico del Ca’ Foscari Short Film Festival di Venezia e Co-direttore dell’Asian Film Festival di Bologna), Henry Lowood (Curatore per la Germanic Collections e l’History of Science and Technology Collections all’Università di Stanford) e Jenna NG (Professore di cinema e media interattivi all'Università di York).

Tra gli eventi correlati spicca il keynote di Jenna NG nell’ambito dei GAME TALKS all’Università IULM che si terrà il 13 marzo 2019. Intitolato IL MACHINIMA E IL FASCINO DELL'EFFIMERO: GAMEPLAY, LIVE STREAMS E CULTURA DIGITALE, l’intervento esamina l’esplosione di interesse per il live streaming videoludico come attestato dalla popolarità di Twitch, il cui numero di utenti attivi su base quotidiana ha ormai superato i quindici milioni e a cui si aggiungono piattaforme come YouTube Gaming, Mixer e Facebook Live. Secondo NG, il fenomeno dei live stream dei videogiochi è legato a doppio filo al machinima e alle origini della cultura demo e dei replay. Per questo motivo, la ricercatrice definisce il live stream l’evoluzione diretta del machinima. NG propone inoltre un inquadramento teorico dei media a schermo che persegue l’imperativo estetico del realismo illuminando le relazioni tra il cinema neorealista e la machine vision.

Promossa dal Comune di Milano, Assessorato alla Trasformazione Digitale e Servizi Pubblici, la Milano Digital Week propone le più interessanti iniziative che stanno trasformando il lavoro, il tempo libero, la formazione e le dinamiche della progettazione e della produzione attraverso le tecnologie digitali. Un’opportunità di riflessione e confronto per cittadini, aziende, istituzioni, università e centri di ricerca.

Curato da Matteo Bittanti (Direttore artistico) e presentato da Gemma Fantacci (Direttore della Comunicazione), il MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL 2019 è stato organizzato dal Master of Arts in Game Design dell’Università IULM. Le proiezioni si svolgono nella Sala dei 146 dello IULM Open Space. L’ingresso è gratuito previa registrazione.

EVENT: MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL (MARCH 16 2018)

MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL

The aesthetics and politics of video game cinema: IULM University hosts the first edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL.

MILAN - On Friday March 16, 2018 from 6.00 p.m. in the Sala dei 146 (IULM OPEN SPACE) IULM University will host the first edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL, an official event of the Milano Digital Week 2018.

A follow-up to the 2016 exhibition GAME VIDEO/ART. A SURVEY organized by IULM University, this retrospective features a selection of machinima produced by international artists. Situated at the intersection between video games, experimental cinema and video art, machinima is an audiovisual genre that defies easy categorizations. Artists appropriate and modify pre-existing video games to create visually idiosyncratic experiences.

The first edition of the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL features Tayla Blewitt-Gray (Australia), Alan Butler (Ireland), Jacky Connolly (United States), Thomas Hawranke (Germany), Jonathan Vinel (France), and Eduardo Tassi (Italy) among others. A surprise screening will be announced the day of the festival. By hijacking Grand Theft Auto, The Sims, and other titles, these filmmakers created digital shorts focusing on such themes as sexuality, politics, alienation, creativity, and violence.

Curated by Matteo Bittanti, the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL is presented by Laura Carrera and Gemma Fantacci, students of the Master of Arts in Game Design of IULM.

Sponsored by the City of Milan, Department of Digital Transformation and Public Services, the Milan Digital Week (March 15-18, 2018) celebrates the driving forces that are reshaping work, leisure, and learning. By highlighting the interplay behind production and consumption made possible by digital technology, MDW aims at connecting citizens, companies, institutions, universities, and research centers.

MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL

March 16th 2018

From 6.00 p.m. to 7.30 p.m.

IULM Open Space (IULM 6)

Via Carlo Bo 7

20143, Milano

Free and open to the public, upon registration

milanmachinimafestival.org

Hugo Arcier (Photo courtesy of Hugo Arcier)

HUGO ARCIER: "WE ARE LIVING IN A SIMULATION"

In this interview, French artist Hugo Arcier extols the joys of virtual hiking, explains why game playing is usually a “passive” activity, and what it really means to be stuck in limbo.

Hugo Arcier is a French digital artist - or, rather, “an artist in a digital world” - who uses 3D computer graphics to create videos, prints, and sculptures. Initially interested in the field of special effects for feature films, he worked on several projects with Roman Polanski, Alain Resnais, and Jean-Pierre Jeunet. This practice has allowed him to gain a deep understanding of digital tools, in particular 3D graphic images. His artistic works have been exhibited at international festivals (Elektra, Videoformes, Némo), galleries (Magda Danysz, Plateforme Paris, etc.), art venues (New Museum, New Media Art Center of Sichuan Fine Arts Institute, Le Cube, Okayama Art Center, Palais de Tokyo, etc.), and several contemporary art fairs (Slick, Variation).

Arcier's LIMBUS (GTAV) (2015) is featured in TRAVELOGUE.

Hugo Arcier, Ghost City, 2016

"A video installation by Hugo Arcier with an original music by Bernard Szajner Draws on De rerum natura of Lucrece, the installation Ghost City is built around a reinterpretation of the set of the famous game GTA V. The spectator is plunged into an environment without any population. The focus is put on architectural and graphic elements. It is a meditative and captivating experience. This virtual universe solicits both the present (the experience of the artwork) and the memory. This installation will be visible first at my solo exhibition "Fantômes numériques" at Lux Scène Nationale. "

Matteo Bittanti: One question I ask all the artists involved in TRAVELOGUE is to describe their personal relationship to simulated and real driving, that is, to video games and cars (= “concrete”, metal-and-plastic automobiles). According to Marshall McLuhan and Charissa Terranova, as a bodily extension or prosthetic, every technology - including cars and digital games - simultaneously augments” and "amputates" human beings. How do you address this tension in your work?

Hugo Arcier: In regard to my personal relationship to video games, I have to confess I consider myself a hardcore gamer. In fact, I play games nearly every day. My passion for gaming goes back to the 1980s. I discovered video games on my cousin’s Amstrad CPC. It was a true revelation. I started with adventure games, then moved onto beat’em ups and platforms. I begged my parents to purchase me this machine, but when we went to the store, the seller was adamant about PCs. This new platform was relatively new at the time and more powerful. So we bought a personal computer, but I was disappointed because the graphics were not as good as on the Amstrad. But things changed, as you know. Home computers eventually disappeared, while PCs became the ideal gaming platform. I have been a PC gamer since then. What fascinates me most about games is their environments. Games are a spatial medium: this is why I am particularly attracted to open worlds: there is nothing I like more than exploring digital places. I am also attracted to first-person shooters. I consider myself a virtual hiker. To me, playing a games means to explore, to take photographs - screenshots - and to scrutinize everything that I encounter. When I play, I eventually abandon the main, imposed narrative to go off on a tangent. I do not own a car since I live in Paris. Paris does not like cars at all: the traffic is insane and parking is nearly impossible. I use my bike and public transportation to go pretty much everywhere. And let’s face it: combustion cars are a relic of the past. They are noisy and cause massive air pollution. Their main byproduct is smog, which in turn causes lung cancer and other health related issues. All that cars produce is detrimental to human beings. Recently I saw a short documentary from the INA archive that discusses an electric car invented by a French engineer called the electric egg. It was available in 1942. I found this document utterly fascinating: it somebody were to launch such a model today, it would be as futuristic and modern as it was back then. I cannot understand how and why combustion cars have lasted so long. It is as if we were still using the Amstrad today: a complete anachronism.

Séquence Renaissance, 2012. Lighting/rendering of the sequence by Hugo Arcier.

My approach to virtual cars in gaming and 3D animation is very different. These cars exist in a space where they cause no health issues to humans. I love simulated driving: it is a form of pure escapism, devoid of any “real” consequence. I do not fetishize cars per se. When I play a game I am more attracted to arcade driving styles, which emphasize spectacle over verisimilitude. There is something truly hypnotic in virtual driving. Technology has positive and negative consequences, but - all things considered - I disagree with McLuhan that it “amputates” human beings. Technology has mostly positive side effects. It does expand human capabilities considerably. I do not have any faith in organized religions. I am extremely skeptical on anything that evokes the notion of the supernatural. At the same time, I am fascinated by the idea of a technologically enhanced life. Concepts like transhumanism have a certain appeal to me. I admit that my optimism is a weakness of mine. I do recognize that technology is akin to a secular religion. What truly concerns me, in the long term, is that technology can make human beings lazy, complacent, and thus less intelligent. Their technological aids can become like crutches. We increasingly use highly sophisticated devices and we have no idea how they are produced. Artists are a particular kind of user: they want to know how things are done. Artists must show what lies underneath the surface of particular technology. This is why I developed projects like the Limbus series: to show games from an unusual perspective, to disintegrate the alleged realism of virtual worlds. My recent installation, Ghost City, is about the fact that virtual worlds are shallow universes, literally, like empty shells.

Hugo Arcier, Limbus (Rage), 2011

"Sometimes a bug in a video game can be magic. It gives the keys to a normally unexplored area, beyond, in the limbo of the game.

Parfois, un bug dans un jeu vidéo peut être magique. Il donne les clefs d’une zone en marge, normalement inexplorée, située au-delà, dans les limbes du jeu." (Hugo Arcier)

Matteo Bittanti: In the TRAVELOGUE exhibition, we showed LIMBUS (GTA V) (2015), the follow up to LIMBUS (RAGE) (2011). These two works exemplify the difference between "found" and "enacted" glitches. What does the glitch represent to you? A fragment of the technological unconscious, a symptom of the true nature of simulation, a purely aesthetic style or something else altogether? And what is the "limbo of the game" you mention?

Hugo Arcier: Video game glitches are very important because they grant the user access to something that is usually inaccessible, something users are generally not allowed to see. Thus, glitches produce a powerful distancing effect: the player is abruptly reminded that each simulation is an artifice, a conceit, and a deception. Although gamers are usually considered “active” in their interaction, they are mostly passive. The glitch awakens the player from her torpor: suddenly the player realizes that the ultra-realistic world she is immersed is a “just a game”. This distancing effect - almost like an epiphany - is relatively uncommon in other media. In movies, this effect can be encountered only in auteur (think Jean-Luc Godard) or amateurish productions (Z-movies and the likes), but in video games, this phenomenon happens even in triple AAA productions, the equivalent of a highly polished Hollywood blockbuster. To create the Limbus series, I specifically looked for a point of view outside the level of the game. I took advantage of a technical optimization technique of video game production: every polygon is single sided, so if you see something from the wrong angle it becomes transparent. This conundrum leads to something visually fascinating. If you can see the level from below, the ground completely disappears, but the characters and props behave as if nothing happened. I have discovered this glitch completely by chance and I captured it to create the first Limbus, in 2011. The process entailed a documentation of the glitch encountered in the video game Rage via screen capture. I felt I had to save something that a subsequent patch might have erased forever. To create the second Limbus in Grand Theft Auto V, I intentionally used a cheat mode: I made myself invincible and I teleported myself to a specific area of the game. But the process was not necessarily easy. The cheat mode did not always worked well and the “perfect spot” was hard to find. In regard to your question about the “limbo” dimension of a game, to me it’s basically a place outside the game itself. But limbo has religious connotations as well. It is a synonym of purgatory: a place where the soul is temporarily “parked” after someone’s death. It’s an in-between area, a liminal space. The video game equivalent to me is when you reach a point where you cannot proceed in the story as if you were dead: you can only wander around and look in a sort of out-of-body experience. In short, to be stuck in limbo means to be waiting for something to happen in a grey zone, not hell, not paradise. Something else altogether.

Hugo Arcier, FPS, 2016

"An interactive installation by Hugo Arcier Music by Stéphane Rives and Frédéric Nogray (The Imaginary Soundscapes) FPS is a post November 2015 Paris attacks art piece. The artist deals with blindness hijacking video game codes, in particular of first person shooter game. The only visible elements are pyrotechnic effects, gunshots, muzzles flashes, sparks, impacts, smokes. All these elements reveal a decor and impersonal silhouettes, innocent persons denied by the subjectivity of the character we incarnate. From dark to light, a blindness is replaced by another one. Gunshots after gunshots a memorial is created before our eyes.

FPS Installation interactive de Hugo Arcier Musique de Stéphane Rives et Frédéric Nogray (The Imaginary Soundscapes) FPS est une œuvre post-13 novembre 2015. L’artiste y traite du thème de l’aveuglement en détournant les codes du jeu vidéo, en particulier du jeu de tir à la première personne (first person shooter). Ne sont visibles dans l’œuvre que les effets pyrotechniques, coups de feu, traînées, étincelles, impacts, fumées. Tous ces éléments révèlent en creux un décor et surtout des silhouettes impersonnelles, personnages innocents niés par la subjectivité du personnage que l’on incarne. Du noir à la lumière, un aveuglement en chasse un autre. Coup de feu après coup de feu se crée sous nos yeux un mémorial." (Hugo Arcier)

Matteo Bittanti: The notion of simulation occupies a central position within your practice. Your work brings to the surface the ideologies of digital technologies that we usually take for granted, from first-person shooters to action games, from computer animation to machine learning. How do you approach these issues as an artist, that is, as opposed to a scholar who is interested in using words and concepts to illuminate a process or a documentary filmmaker whose main goal is to document a situation via an edited audiovisual recording? How do you grasp and communicate the essence of computer graphics and algorithmic worlds through your artistic practice?

Hugo Arcier: An artist focuses on the same subjects that may fascinate a scholar or a filmmaker, but with a less theoretically-oriented approach. Art is not about explaining something. Art is about addressing the sensible. Here, the emotional and the experiential always come first. They may lead to reflection - which in turn leads to enlightenment - but only at a later stage. My artistic practice focuses mainly on computer graphics. As you know, the video game is just one of the many artifacts using computer graphics. I try to capture its essence by applying different strategies. First of all, I operate through a process of dissection: I remove layers of data until I can show one single, bare element in each series. In a sense, my modus operandi is similar to an autopsy: this is how one learns about anatomy. You start from a very complex, opaque, difficult to understand whole - a body - and then you start to take it apart, cutting smaller sections. Secondly, my goal is to make computer graphics and algorithms visible, legible, and recognizable. In fact, these elements tend to be generally invisible, under-the-hood so to speak. Even in my more realistic projects like the film Nostalgia for Nature, the simulation is rendered visible. This was meant as a meta-discourse on computer graphics, in a self-reflexive manner, a film-within-a-film.

Hugo Arcier, Nostalgia for Nature, 2012.

A co-production Hugo Arcier and Le Cube Music of Cocoon, “Paint it Black” (Optical Sound) Voice over written and said by Agnès Gayraud English translation by Dylan Joseph Montanari Spanish translation by Open This End (OTE), Guillermo Remón Garcia.

Nostalgia for Nature is a true sensory experience, a film composed entirely of computer-generated images. It immerses us in the spirit of its protagonist, an ordinary city dweller who recollects moments and scenes from his childhood, all inextricably tied to nature. Guided and accompanied by off-screen narration, these flashbacks intermingle, diffracted by his memory. The film, however, rejects Manichaeism, revealing nature as far from idyllic…rather, as somber, at times ominous, but always fascinating and beautiful. The paradox of representing nature through computer-generated imagery lies at the heart of the film. It is also where its nostalgia resides. The film is a declaration of love to the incredible forms engendered by nature that we no longer see or, rather, no longer know how to see.

Nostalgia for Nature est un film sensoriel entièrement réalisé en images de synthèse. Il nous plonge dans l’esprit d’un personnage citadin qui se remémore des moments de son enfance liés à la nature. Guidés par une voix off, ces flashbacks s’entremêlent, diffractés par sa mémoire. Le film n’est pas manichéen, il montre une nature – loin d’être idyllique – sombre, parfois inquiétante, mais fascinante et belle. Le paradoxe de représenter la nature par des images de synthèse est au cœur du film. C’est aussi là que se situe la nostalgie, et le film est une déclaration d’amour aux formes incroyables engendrées par la nature et que l’on ne voit plus ou que l’on ne sait plus voir." (Hugo Arcier)

Matteo Bittanti: Terms that "ghosts", "nostalgia", and "disappearance" recur in your works. Does simulation replace reality, as Jean Baudrillard and Paul Virilio argued? Or is simulation just another layer, another mode of being? And why is it so important for you to document this phenomenon through your artistic work?

Hugo Arcier: These notions - disappearance, substitution and more - are absolutely central in my work. I don’t know exactly what qualifies as “reality” any longer and probably I don’t care because what is important is what you experience, what you see, what you hear, and - at a deeper level - the information stored in your brain. From this vantage point, we can say that simulation replaces reality. Simulation has already won the battle because it is more malleable, efficient, flexible. You can’t take any risk in real life: people don’t like that. They like “safe”. Many years ago, I was commissioned a project to make a very realistic tree in computer graphics. That did not make much sense to me: so I asked “Why don’t you just shoot a real tree with a camera?”. They responded, somehow annoyed, that it is cheaper to make a tree in computer graphic that paying a filmmaker and a professional crew to film it. Plus, you need to spend time finding the perfect tree with all the leaves in the right spot, a certain kind of trunk… The shooting may be compromised by real-life situations like unpredictable weather conditions (rain, wind, low light etc.). In short, they said, a simulated tree is better than a real tree. When I heard this explanation, I was shocked. I realized I just witnessed a turning point. As an artist, I chose to work with the medium of computer graphics because that puts me in the trenches, in the frontline of the contemporary. To me, it’s essential to document the transformation of our world into a massive simulation and to accomplish such goal there is no better tool available than the simulation itself.

Victor Morales. Photo credit: Peter Yesley

VICTOR MORALES: "GAME MODDING IS A CREATIVE HIJACK"

In this interview, Victor Morales explains why video games can activate our deepest feelings and why game engines are the equivalent of brush and painting.

Born in Caracas, Venezuela, Victor Morales received a Law Degree from Universidad Catolica Andres Bello in 1990. In 1992, Morales completed a Master’s degree in Technology Applied to the Arts at New York University’s Gallatin Division. He spent more than a decade in New York City. Since 2003, Morales, “has been obsessed with the art of video game modifications and has implemented different game engines into most of the works he has participated in or created.” His performances with game engines (in particular, the CryEngine) have consistently challenged the nature of simulation. Morales has performed a number of solo shows in art galleries, festivals, and events, including Performance Space 122, The Little Theater in New York City, The Collapsable Hole in Brooklyn, and Gessner Allee in Zürich, Theater Freiburg, and The Hau in Berlin, where he now lives and works.

Morales's video 30 Seconds or More: City Stroll was featured in TRAVELOGUE.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe the process behind the 30 seconds or more series in general and City Stroll in particular?

Victor Morales: In the 30 seconds or more series, my goal was to push the envelope as much as I could, so I decided to make an animation a day for an entire month month using exclusively the CryEngine. I followed just one rule: each video had to be longer than a regular TV commercial. There was another prerequisite: I wanted each piece to be sound-reactive and I used outstanding music produced by Norwegian artist Pal Asle Petersen. So in almost all of the pieces there is an audio-reactive element, sometimes obvious, sometimes not so evident. City Stroll was for me a contemplation of an urban environment, always moving, made of straight lines, bright colors, and particle systems.

Victor Morales, eva, 2016, 4' 06". Experimental sleepy video Music by Pal Asle Petersen and voice by Jessica Weinstein, with a little treatment

Matteo Bittanti: TRAVELOGUE focuses on the notion of driving - real and imagined, represented and simulated, utopian and apocalyptic. What is your relationship to cars and car culture? Do you drive, and if so, what do you see through your windshield?

Victor Morales: To drive is to be in your own cocoon, where you can control the soundtrack if you are alone or have the deepest conversation you can imagine as you make eye contact through the landscape... Moving on wheels at fast speed offers a kind of pleasure, a bizarre pleasure, a peculiar mix of power and comfort as you move through different scenarios... Each trip is a story.

Victor Morales, 7bt8, 2015. 01' 27". Beat by Miguel Toro.

Matteo Bittanti: You use game engines as a painter uses the brush and paint. What is the potential - but also the biggest limitation - of working with this medium, i.e. game engines?

Victor Morales: Like painting, video games could awaken deep emotions and psychological dynamics hidden within our personal and collective selves. The biggest limitation of a game engine lies in its operational complexity. Like Francis Bacon's wish, I wish I could just grab a hand full of paint and throw it on the canvas and make a piece with one move.

Victor Morales, Fell so Free, 2014, 01' 56"

"Yet another flying dream. I was doing some cutting of some GTA V old footage i never used... and funnily enough this sequence matched nicely with Johnny Colon, without any edits." (Victor Morales)

Matteo Bittanti: By your own admission, since 2003, you have been "obsessed with the art of video games modifications". Can you explain this obsession? What do you find so engaging about deconstructing and reconstructing video games? To modify a game is for you an act of détournement, in the Situationist sense, or something else entirely?

Victor Morales: Yes, as you said, game modding is a hijack, a kind of hacking. Modding means to penetrate someone else's universe and make it your own. In a way is a precursor of social media and the so-called "user-created content" buzz/word/hype... But it is also much more engaging and complex than applying an insta-filter to whatever you capture with your smartphone. You must do some research, try and fail many times, scrutinize forums in search for clues, ask questions, and experience the strange feeling of being called a noob by a twelve year old kid and then you must work for hours and hours in order to get something going... I freaking love it, i can't deny it... I do not do it as much as I used to, but sometimes a bit of GTA modding really gets me going.

Matteo Bittanti: Your life can be defined as nomadic: you were born in Venezuela, spent more than a decade in New York, moved to Berlin.. Your experiences are as fascinating as your artist practice. Which place or places do you consider most compatible with your artistic sensibility? Where did you find the most welcoming, receptive, engaged community?

Victor Morales: I am now back in New York, but yes I do travel a lot... to be honest, I think video game art is still not considered with the seriousness it deserves: there are not enough places to show work, to meet other artists, to do residencies... There is simply not enough interest from museums, critics are for the most part unprepared, and so on... In general I find Europe to be much more receptive, but that applies to all kinds of arts. After all, Europe likes art... Maybe there will be a breakthrough sometime in the future and digital artists will get more resources to make their art without having to think on how to sell it... Or maybe it's just my pipe dream.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman

JEAN-BAPTISTE WEJMAN: "VIDEO GAMES ARE RAW MATERIAL THAT ARTISTS CAN - AND SHOULD - EXPLOIT"

In this interview, French artist Jean-Baptiste Wejman explains why Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe's works are "game-like" and why simulations and fictions are deeply intertwined.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman is an artist living and working in Toulouse, France. He received a Master of Arts in Fine Arts at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts de Bourges in 2014. An amateur photographer in his teenage years, he decided to become an artist at the age of 17, after attending a solo show by Mircea Cantor at FRAC in Reims. Influenced by artists such as Ryan Gander, Philippe Parreno, Pierre Huyghe, Cory Arcangel, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, and Wolfgang Tillmans, he is interested in developing new practices of art and thinks that lacking a definition of art is, in itself, the most powerful engine for conceptual aesthetic thinking. His work has been exhibited internationally, including 35h (2015), a group show in Champigny-Sur-Marne near Paris, The Graduals (2012) at Traffic Arts Center in Dubai, and 43/77 (2009) in Bourges.

Wejman's installation Concentration Before a Burnout Scene is featured in TRAVELOGUE.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you briefly describe your education and upbringing?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: I was lucky enough to experience an ordinary childhood, like many other kids growing up in the Nineties in France. As a teenager, I never envisioned that one day I would become an artist. I spent the best years of my youth playing video games, riding my BMX bike, reading and collecting used books, and listening to as many audio cassettes as I could. When I was still young, I had the chance to try my hand at photography with an old camera. I discovered Art in school, between the age of 11 and 15. I have to express my gratitude to the French educational system: it made me realize that art was an exciting field, not a moribund, boring discipline. I chose to concentrate in Fine Arts during my high school years. Around that time, I visited my first exhibition of Contemporary Art and that event changed my life. I had the opportunity to take excellent courses in Art History and I developed my first projects. Today, I keep them hidden in a remote space of my parents's garage! Back then, I enrolled in several science-based courses, but my passion for art was too strong to resist. Luckily, I was accepted by L'Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts in Bourges. Those were intense times. This is when I began to focus on a set of artistic concerns and to fully develop my art practice. I was very interested in research: I began investigating the status of the image, the deep meaning of photography, what lies behind the surface. My interest was definitely conceptual. In school, I kept asking myself: "What is my role as an artist?", "What is the goal of making art, today?", "What's the point in creating yet another image in the Twenty-first century?", "What kind of exposure can an artist's project receive?" and many more questions like these. Meeting like-minded peers was essential. Students, teachers, assistants, fellow artists... The conversations were intense! L'Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Arts gave me the chance to immerse myself in a lively art milieu and to participate in engaging discussions, stimulating debates, and constructive critiques. Finally, in 2014 I received a Master of Arts with honors. Since then, I have been developing my artistic activity.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Reprise, reprise déprise, 2016

Matteo Bittanti: Why did you begin to incorporate video games in your practice? What do you find fascinating about this medium? Its interactivity? Agency? Aesthetics? Theatricality? Or are you more interested about the online communities that blossom around digital games?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: These are all excellent questions. Why? Well, for a long time I thought that the boundaries separating Art from "everything else" were clear, rigid, and somehow inviolable. Universal laws, so to speak. However, as time went by, I was forced to rethink my assumptions and to question my own prejudices. I was influenced by several critics and thinkers. One is Paul Ardenne, who believes that art should always be contextualized. He says that we must abandon the notion that each artwork is an autonomous object, existing in a vacuum. Ditto for Hal Foster, whose emphasis on theatricality forces us to think about artistic situations as always spatially situated. Since the Nineties, these discussions have evolved considerably: they might have taken new forms, but they certainly have not ended. Initially, what fascinated me about the role of video games within the contemporary visualscape was the ongoing debate around their status as art. As you know, "Are video games art?" is a question that dominated the conversation in the late Nineties and early Zeroes. For several critics, video games are just commercial artifacts, the byproduct of a creative industry akin to Hollywood. Other believe that games are still in their infancy, and, as such they are "under underdeveloped": once artists and intellectuals start unpacking their true potential, they will evolve in unexpected ways, subverting the conventions and clichés of mainstream productions. I began incorporating games in my practice around 2011 when I recognized their cultural value. To me, they were raw material that could - and should - be exploited by artists. Today, it is obvious to me that digital games are just another way of making art. We are overwhelmed by a staggering production of fiction, images, and interactions. We now posses the technical means to navigate virtual spaces. In a sense, we made Leon Battista Alberti's dream finally happen. My generation grew up watching a world unfold not outside "windows" but on Windows, jumping from one tab to another, playing with all sorts of information, assuming different identities and characters. As an artist, I wanted to partake this conversation and to experiment with new media. When I incorporated games in my artistic practice, the process felt natural, almost automatic. Perhaps even necessary.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Une table modifiée pour une machine qui génère un monde qui génère un personnage qui génère un voyage, 2014

Matteo Bittanti: Digital games often create parallel, alternative experiences for their users. How do you relates to the complex relation between reality and simulation? How do you address this tension throughout your work in general and specifically in Concentration Before a Burnout Scene?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: The complex relationship between reality and simulation? This is where all the traditional questions of art clash and collide! Making pictures, chasing mimesis, imitating the real... And this is the reason why video games are so exciting. They force us to confront, once again, the notion of realism. And yet, we must not forget that since the early days of game development, many designers rejected realism in toto, offering instead alternative, more abstract, oneiric experiences. They questioned the notion of aesthetics in art through an image-based form of production. I must also add that, to me, the concept of simulation is closer to the broader concept of fiction. Not only these two notions have strong ties, but they inform each other, they are mutually reinforcing. In my practice, fictions act as simulations. For example, my video Concentration Before A Burnout Scene can be read on several levels. Initially I chose GTA San Andreas because I was fascinated by the very idea of the open world. This is where simulation truly matters. I produced this video by recording my own experience - mediated by an avatar - within the game world. This project qualifies as a machinima. At the same time, I selected a specific context and time frame within the game to extract some elements and to perform a loop. Concentration Before A Burnout Scene depicts the game in a static moment. It is a false movement stuck in an infinite time loop. In short, I simulated play time. Concentration Before A Burnout Scene is not about the "real" game, changing, developing and transforming before our own eyes. It is, on the contrary, a dramatization which offers the viewer the chance to experience an alternative experience of time. A simulated time that produces a duration in the so-called real world.

Jean-Baptiste Wejman, Live Wire Introduction, 2014

Matteo Bittanti: Do you consider yourself a gamer? Do you play videogames? If so, what titles do you find intriguing and stimulating, both, as a gamer and as an artist?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: Yes, I am a gamer, but a rather casual one. I do not have time to play all the games that I want. For instance, I did play Fallout: New Vegas. Not assiduously, like a dedicated gamer, but occasionally, like someone who finds himself fascinated by something he previously dismissed as "trivial". Thanks to emulation, I discovered old Sega Megadrive and SNES games that I could not play growing up because I found gaming too time consuming. Back then, I was always too busy doing something else, like reading or listening to music. In a sense, I am recapturing a part of my youth through retrogaming... So what are the games that an artist may find interesting? Definitely Minecraft. This is such a creative title, one that uses the very idea of open world in the most sophisticated and empowering way. Another game that truly fascinated me is The Stanley Parable: it was such an incredible gaming experience. There is little action, almost no gameplay. Just a voice that speaks to us, opening us up to almost endless possibilities. This is a self reflexive game, a game that questions itself through the medium of the video game. Very meta indeed. It was such memorable experience! Another title that blew me away is Undertale. This game is a tour de force. Using very simple technical means, this game produces a perfect narrative, engaging the player like very few other titles. Undertale breaks, or rather smashes, the fourth wall. It reminds me of something that David Lynch might have dreamed. You meet these amazing strange characters, and yet the world seems quite consistent. It makes sense even when it should not. When people ask me if there are games that offer experiences comparable - if not superior - to those produced by the best books, films, or paintings, I usually mention these three...

Matteo Bittanti: How do video game aesthetics affect the overall impact of your work? What comes first when you are developing a new project, the concept or the medium?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: Game aesthetics are truly fascinating because they link the narrative component to the gameplay. They are inseparable. Take Super Mario Bros.. Considered in itself, its universe is completely incoherent. The world that Mario inhabits is just a pretest to play. I mean, what is the deal with a mustachioed plumber who must rescue a princess in a strange world populated by flying fish and turtles? Even as an interactive fairy tale, it makes little sense. It's the gameplay that justifies the narrative. It's the action that makes the scenario, so to speak. I like to analyze video games in the same way that I examine a traditional work of art. I must understand the creator's process to fully appreciate a game. Consistency is by far the most important aspect of a game. The player must understand the logic of the simulated world. It cannot be random. Even randomness must have some coherence! And that's my challenge as an artist. How can I create works and exhibitions that offer situations where the public can establish a relationship with what I present? Is my world "consistent"? I often think of Pierre Huyghe and Philippe Parreno's works. They create game-like spaces, spaces filled with characters, objects, and situations. Their works come with links, attachments, and identification processes. The same elements are pervasive in video games. These aspects deeply influence my own work. When I develop a new project, the concept is often the starting point. I try to consider how the final aesthetic position will engage the viewer. So I established a methodology according to the situation to produce a coherent "gameplay/scenario" that can be translated in an exhibition as "wandering/narrative".

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe the process behind the production of Concentration Before a Burnout Scene?

Jean-Baptiste Wejman: As I mentioned before, I chose to work with GTA San Andreas because at the time it seemed like the best game simulating the real world, at an architectural, narrative, social, and spectacular level. In short, this is a game that contains several layers of meaning and contexts. Additionally, GTA San Andreas allows emergent gameplay. I was looking for a space within the game that evoked the look-and-feel of film. A place where I could shoot a movie like Bullitt. I navigated the spaces of this virtual metropolis for weeks, seeking the perfect spot and finally, I identified the ideal area, located between the suburbs, stuck between a residential and an industrial zone. So I placed the main character CJ here in a car I've chosen because it resembled the archetypical muscle car - a Dodge Charger or a Ford Mustang - that one encounters in these films. I set my camera to capture the perfect angle, using a panoramic POV. The décor of the city, the visual clichés of the American urban environment were all in place. Then I started to capture the gameplay. At this point, I was working on a computer and I could easily capture a video source. I caught several sequences of twenty minute intervals. The challenge then was to create a short loop. The requisite was that the smoke exhaust and the ambient light must appear "natural". I produced a first version in MPEG 2 format in 2011. But for this exhibition, TRAVELOGUE, I reworked the source file to produce another video in 1080p. I consider this a form of digital restoration. It was a long process which took weeks. Although it may not seem like at first glance, I chose to show a passage where the heat effect distorts the image. I think this visual effect can distort the sense of time. The title is an integral part of the work. It contains several possible readings. It is clearly descriptive: what we see is, indeed, a character waiting in his car, idling, the engine running. He may be preparing to leave and make a U-turn in the middle of the road. But it also describes the expectation of the viewer. Lastly, it forces the viewer to concentrate on image and such concentration has limitations. It's a game on the expectation played on the viewer. A pending action, a possible story, an endless wait.

William Beaudine, Design for Dreaming, 1956

SPECIAL SCREENING: DESIGN FOR DREAMING

On the closing day of the exhibition - September 11 2016 - we screened William Beaudine's masterwork, Design for Dreaming, a short film produced in 1956 for General Motors.

DESIGN FOR DREAMING (1956)

Video, color, sound, 9' 17"

"Produced to bring the 1956 G.M. Motorama to audiences unable to see it in major cities, this film introduces the new 1956 cars, Frigidaire's "Kitchen of Tomorrow," and the electronic highways of the future. G.M.'s "dream cars" of the 1950s, including the Oldsmobile Golden Rocket and the turbine-powered Pontiac Firebird II, are also displayed. One of the more self-consciously surreal films in our collection, Design for Dreaming often looks like a Hollywood musical. A Fifties-style sleeping beauty is awakened into a dream by a magician dressed in tails who hands her an invitation to the Motorama at New York's Waldorf-Astoria Hotel." (Rick Prelinger)

WILLIAM BEAUDINE (U.S.A.)

William Beaudine (1892 – 1970) was an American film actor and director. He was one of Hollywood's most prolific directors, turning out films in remarkable numbers and in a wide variety of genres. Beaudine was a low-budget specialist, forsaking his artistic ambitions in favor of strictly commercial film fare, and recouping his financial losses through sheer volume of work.

TRAVELOGUE PHOTO GALLERY

Click here to see the TRAVELOGUE photo gallery.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, Dismantled Data, 2016

BOB BICKNELL-KNIGHT: "EVERY DAY WE REPLICATE THE IDEA OF WHAT LIFE SHOULD BE LIKE"

In this interview, British artist Bob-Bicknell-Knight discusses the effects of simulation on everyday life and the illusion of control of digital media.

Bob Bicknell-Knight is a London-based artist working in moving image, installation, sculpture and other digital mediums. Surveillance, the internet and the consumer capitalist culture within today’s society are the main issues surrounding his work alongside an intense fascination in the various cultures associated with video games and online communities. He explores these themes using tools and technologies, which are relatable but not restricted to art.

His 2016 artwork Simulated Ignorance is included in TRAVELOGUE.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you briefly describe your education and upbringing?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: Until a few years ago I had lived solely in the English countryside, only recently moving to London to undertake a degree in Fine Art at Chelsea. I now find myself focusing on ideas surrounding internet surveillance and video game aesthetics/ideas. A lot of my formative years were spent going on walks and exploring virtual worlds, occasionally going to museums and art galleries when I had the chance.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, Consumerist Dissonance, 2016

"This piece considers the utopian relationships and spaces that we encounter within video game worlds and the escapism that is sought out within computer games as well as the futility associated with the accumulation of consumerist products." (Bob Bicknell-Knight)

Matteo Bittanti: Why did you begin to incorporate video games in your practice? What do you find especially fascinating about this medium? Its interactivity? Agency? Aesthetics? Theatricality? Or are you more interested about the online communities that blossom around games?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: I’ve always played and enjoyed video games and have only recently begun to create work about them, due mostly to Jon Rafman and his extensive use of video games and their aesthetics within his own practice. When I saw his work, it was the first time that I realised one could actually make something that was valued, interesting and cohesive with the aesthetic and medium of video games. A lot of the aspects of video games that you’ve mentioned I’m interested in, especially the idea of interactivity and the communities that are formed around certain games. In terms of interactivity, with other forms of media, one rarely has any choice over what happens or any control over the flow of the experience; these are the two unique qualities of video games that sets them apart from standard tv shows or films. Rejecting the passive experience of simply viewing something through a screen is incredibly important to me. This interest in interactivity is hinted at within the installation, Simulated Ignorance, with the presence of a game controller, suggesting a sense of control to the viewer.

The extensive relationships that are formed through various online games are also intriguing to me, just listening to the passion in people talking about a raid in World of Warcraft or talking about a friend they met through Guild Wars definitely hints at the future of how we will interact with one another on a daily basis. A game that combines both interactivity and an online community incredibly well is Cloud Chamber, with the main body of the experience being simply posting on a message board, hoping that your particular ‘theory’ gets up-voted by the community in order to progress to the next level of the game. That progress is dependent on the friends that you make within this online experience is slightly disturbing to me, yet again hinting at possibilities to come.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, An Undignified Failure, 2016

Matteo Bittanti: Digital games often create parallel, alternative experiences for their users. How do you relate to the complex relation between reality and simulation? How do you address this tension through your work and especially Simulated Ignorance?

Bob Bicknell-Knight: At this point the differences between reality and simulation are becoming increasingly blurred in offline and online cultures. Like Jim Carrey in The Truman Show, we find ourselves replicating an idea of what life should be like on a daily basis, often this is subliminally enforced by various medias to cater to the consumer. On the other hand, however, people are becoming more and more detached from their online self, creating multiple personas to embody when browsing ‘Web 2.0’, not fully realising the implications of such acts of apparent transgression. In my installation work, Simulated Ignorance, I’m seeking to highlight the multiple choices one has by providing the illusion of choice that the viewer is presented with, both challenging and confusing their preconceptions of violence and free will in video games.

Bob Bicknell-Knight, Fabricated Loss, 2016

"A work exploring the tedium of daily life, the relationship between humans and technology as well as the idea of community." (Bob Bicknell-Knight)