In this interview, Canadian artist Clint Enns reveals his passion, perhaps even obsession, for Andy Warhol's Empire, obsolete media, and video art.

Clint Enns is a video artist and filmmaker living in Toronto, Ontario. His work primarily deals with moving images created with broken and/or outdated technologies. His work has shown both nationally and internationally at festivals, alternative spaces and microcinemas. He has a Master’s degree in Mathematics from the University of Manitoba, and has recently received a Master’s degree in Cinema and Media from York University where he is currently pursuing a PhD. His contributions have appeared in Leonardo, Millennium Film Journal, Incite! Journal of Experimental Media and Spectacular Optical.

Enns's PREPARE TO QUALIFY is featured in TRAVELOGUE.

Matteo Bittanti: What can you share about your artistic background? I find very interesting that you have received Master’s Degree in Mathematics. Is your practice as an electronic artist and experimental filmmaker a way of articulating an overlooked side of science, perhaps its unconscious? How does the study of numbers, equations, and formulas influence or even guide your work?

Clint Enns: I began making art when I began my Master's Degree. It was really an attempt to do something other than mathematics. I had no idea that it was possible to make art before that. My best friend and girlfriend at the time, animator Leslie Supnet, pushed me into making my first film. It was SUPER FUN and not very good, but I was hooked. Before that I was a cinephile, but it never occurred to me that I could make something...that is, that it was as easy as putting film in a super 8 camera and pushing the trigger.

While doing my Master's, I began to teach a course called Math in Art. Teaching the course forced me to engage with contemporary art practices and with art history. Currently, I am pursuing a PhD at York University and I am studying the connection between mathematics and cinema. With that, I try to keep my studies separate from my art practice, although I am sure they inform each other. I still view art making as a form of escape. If art making stopped being fun or cathartic, I would probably do something else. In fact, when I first moved to Toronto, I kept being told that I do not take my moving image practice seriously enough or that I wasn't rigorous enough. At the time, it really killed my desire to make moving images, so I started taking photographs and working with found photography. It was really freeing, I didn't have to answer to anybody. Now, I do both.

Clint Enns, 747, 2010

"Chris Burden's 747 re-performed in Grand Theft Auto IV." (Clint Enns)

Matteo Bittanti: Within the field of Game Studies, machinima is usually associated to online fandom, hacking, and modding practices. In other words, machinima is firmly located within the context of game culture. For other critics, machinima constitutes a kind of experimental filmmaking, and, as such, it’s something that should be projected onto a screen, in a dark room, and experienced collectively, offline, possibly in a festival setting. Finally, others consider machinima a genre of video art which is often displayed as a video installation in a White Cube space. You are a prolific writer, an accomplished artist, and an indefatigable curator: What is your personal take on machinima? Can these different notions of machinima coexist and/or inform each other or are they mutually exclusive? Do you use the term “machinima” or do you find it too limiting, as in too video game-centric?

Clint Enns: I don't have much investment in the term machinima, but why shouldn't it exist in multiple contexts? I am personally interested in works that experiment with video games as a medium and in works that treat video games as a form of found footage. It could be argued that Craig Baldwin's 16mm film Wild Gunman from 1978 is one of the earliest examples of machinima (he uses footage from the 1974 game Wild Gunman which made use of a light gun and a 16mm projection). I think you could also argue that Stephanie Barber's 2005 total power: dead dead dead, a 16mm film in which an arcade game, a snack machine and a television engage in a dialogue, is a form of machinima. However, I doubt either of these works are included in the Machinima Archive.

Clint Enns, Gameboy Empire, 2011

"A re-make of Andy Warhol's Empire for Gameboy. This video was captured on a Super Gameboy, although this game is intended to be viewed on an original Gameboy. If you are interested in the source code or the Gameboy rom, both are available upon request." (Clint Enns)

Matteo Bittanti: What do you find so intriguing about obsolete, archaic, and “broken” media? Is your practice a form of media archeology? Are you documenting forgotten technologies, like the Nintendo Gameboy Camera, Super 8, kids' toy cameras etc., through art? After all, you do not simply use found footage, but also problematize issues like media formats, devices, and techniques.

Clint Enns: An academic might read my practice through a media archaeological lens, but I am simply fascinated by old technologies and by cameras that were designed to be easy to use. Ironically, as the equipment gets older it becomes more unstable and more difficult to use, but I like the challenge as well. I also like that these devices come with their own unique aesthetics and as they breakdown produce errors that are difficult to simulate. Although, I am sure I would use a PXL 2000 simulator if a good one existed.

I really feel that art making should be accessible to everyone with a desire to create. Of course, I am not saying all art that is made is good, but that is not necessary the point. To me, art making is form of play, hence my interest in toy cameras.

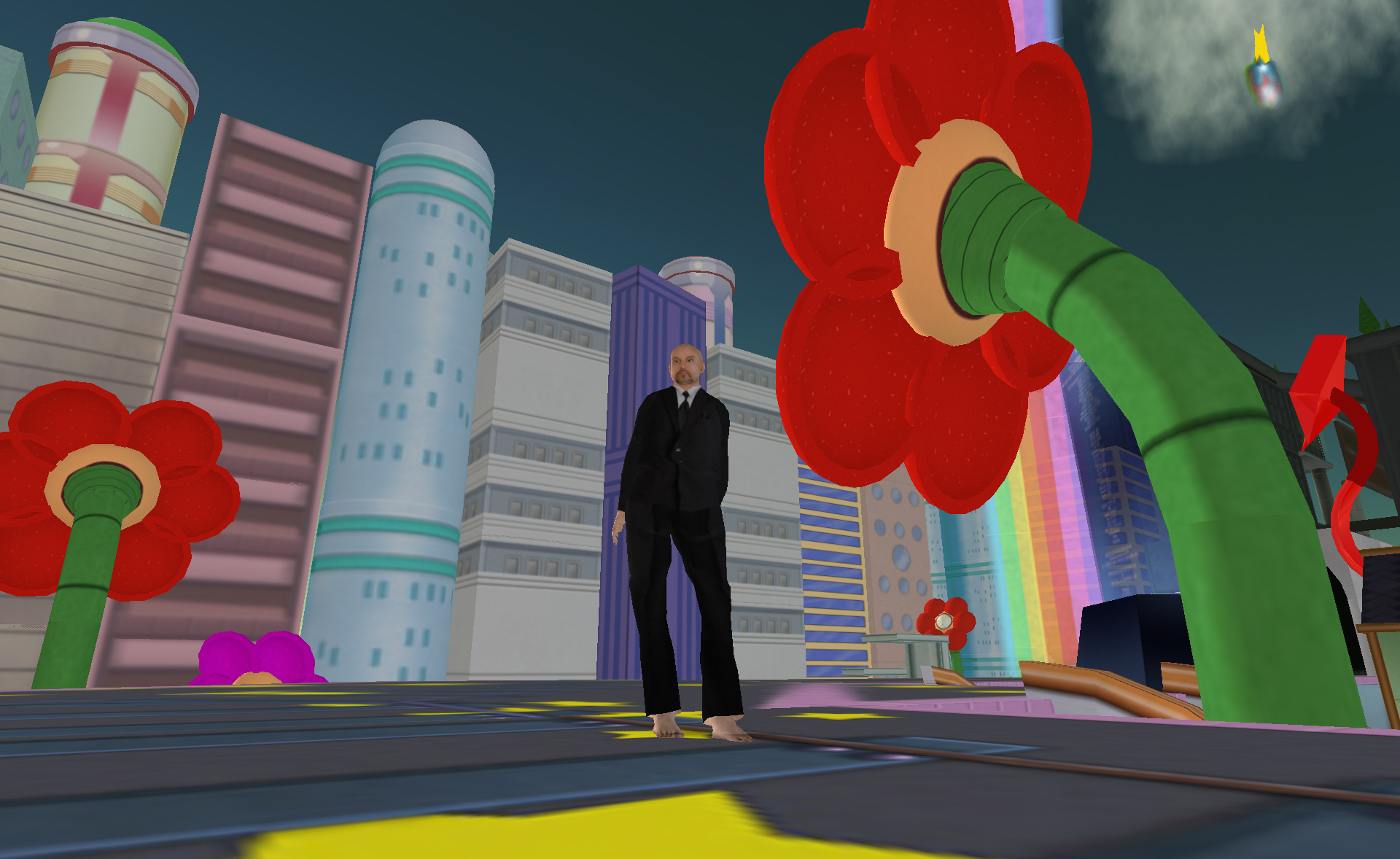

Clint Enns, Rotterdam Tower, 2010

"Liberty City's Rotterdam Tower is based on New York City's Empire State Building. This video is a continuous fourteen minute and twenty-seven second slow motion shot of The Rotterdam Tower in Liberty City. This video was filmed at night between the hours of 8:06 pm and 2:42 am Liberty City time. It is the artists' intent that this video is watched in its entirety." (Clint Enns)

Matteo Bittanti: Can you name some influences in your film and video making? I can see several homages and citations, for example Chris Burden for 747 and Andy Warhol (or Philip Solomon? this one is very meta) for Rotterdam Tower... Is your practice a way to engage in a conversation with the visualscape as a whole?

Clint Enns: I am obsessed with re-making Andy Warhol's Empire and I find it exciting that others are too. I would love it if someone curated an Empire show (Empire Redux) filled with Empire re-makes. An unwatchable film, re-made ad absurdum. My favorite re-make is Gameboy Empire, a Gameboy game for the true Warhol enthusiast. You hit start and see the Empire State Building. Nothing else happens (minus the odd light turning on or off).

Phil and I made our Grand Theft Auto IV remakes around the same time. His was made slightly before mine and is more beautiful; however, mine is more conceptually rigorous. I was totally unaware of Phil's version, but I wish mine had been a re-make of Phil's video!!! In fact, the next time I discuss the work, I am going to claim it is... better mythology. Mine was intended as a shot-for-shot re-make of Warhol's Empire, and was shot during the same hours that Warhol shot his film except time is super condensed in GTA IV. I also slowed down the film, the same way Warhol did. The final work was only 14 minutes, but it was my intent that people watch it in its entirety on the internet, making it totally unwatchable.

I remade Chris Burden's 747 in GTA IV as well. The gesture of shooting at an airplane changes in gamespace. I also remade Burden's Through the Night Softly, as Softly Through the Night. Instead of crawling through glass, I crawled through marshmallows. Ironically, it turns out I was allergic to one of the dyes in the marshmallows (we bought the cheap kind) and I got a near fatal rash and had to spend a few days in the hospital.

The re-make is one way to engage with a historical work through a contemporary lens. I am basically just sweding the avant-garde.

Matteo Bittanti: Prepare to Qualify seems to question the legitimization practices of the art world. To be recognized as ART, the driver (the artist) has to START and win a symbolic competition (the race). But the competition soon implodes, the car (artwork) breaks apart, and we are left with broken pixels and jarring sounds. Who is the driver? Howard Becker? Pierre Bourdieu? Clint Enns? Or someone else entirely...

Clint Enns: I'm not sure at this point. At one point I would claim that the work was self-reflective posing the question: Does breaking video games at the age of 28 constitute being an artist? Now I am even more confused about my own art making practice and its status. If Howard Becker, Pierre Bourdieu or Guy Debord were at the wheel, the world around us would radically change and not simply the screen.

Clint Enns, ♥++, 2012

"A video game that lies somewhere in the realm of text based rpg, digital exploration and guide to sexual enlightenment." (Clint Enns)